Robert Tobias besuchte im April 2013 das erste Mal mit seiner Familie die Orte an denen seine Großeltern lebten, bevor sie aus Deutschland fliehen mussten.

Über seine Reise und die Suche nach der Geschichte seiner Vorfahren schrieb er anlässlich der amerikanischen Holocaust Remembrance Days im Mai 2014 einen Beitrag im Hartford Courant:

Unburying Family’s Painful Wartime Past

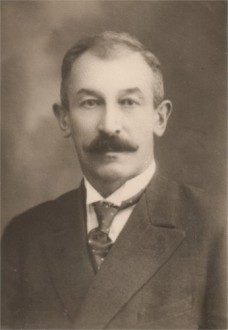

Driven out of their homeland by impending war and religious persecution, my paternal grandparents, Hugo and Irma Gärtner Tobias, and their 4-year-old son, Walter, my father, (now 80 and living in Simsbury), immigrated from Germany to America through Ellis Island on Dec. 11, 1937.

My grandparents never spoke of the Holocaust. It was never discussed around the dinner table or at family gatherings. I never questioned any of them, not about the tattooed numbers on the forearms of some their friends or why they never spoke of the family left behind. There was only silence.

Although I knew about the Holocaust, I chose the path of least resistance and avoided the topic. That changed when the last of my grandparents died in 2005 and I came into possession of a cardboard box containing letters, documents and photographs. I began to uncover their personal and tragic history from which I had been sheltered. I also saw the courage and strength it took to set aside their pain and rebuild their life here.

I never knew the depth of their pain. Perhaps I was too concerned with my needs, insensitive to theirs, too focused on my life and what I needed to accomplish. They’re all gone now — many of their secrets gone with them. And while they never spoke of the Holocaust, I feel that their safekeeping of the cardboard box is evidence of their intention to bear witness.

That box was a turning point for me — I was finally ready to embark on the search for clues and to deal with that time in my family’s history. I wanted to know more.

Last April, my research brought me and my family to Cologne, Germany, my ancestral homeland. It’s one thing to know that family members perished there, it’s quite another to stand in their footsteps.

I knew nothing about my great-grandfather, Hermann Gärtner. He lived in the small village of Ruppichteroth, where he worked as a butcher. He was also, I discovered, an outspoken critic of the Nazi Party. In 1933, he was arrested and held for 10 months for making „false and defacing assertions“ against the National Socialist state. This, the Nazis considered treason.

His story is not unique among German Jews of the time. Like thousands of others, he tried desperately to get a visa to any country that would take him. In the end, his efforts failed.

In a letter written Jan. 6, 1942, addressed to the Jewish Council of Amsterdam, Hermann, who had fled to the Netherlands, pleads for a suspension of his transport back into German hands because of his sciatica. Despite the plea, he was moved to the Westerbork camp in the Netherlands and on Sept. 18, 1942, taken to Auschwitz. On Sept. 24, 1942, at age 66, my great-grandfather was murdered.

How sad it must have been for my grandmother when her father’s letters stopped coming. In the ultimate irony, Hermann fought for the German Reich in World War I. He survived the war, but not the Nazis, who murdered him as „unworthy of life.“

My other paternal great-grandfather, Hermann Tobias, expelled from his home and separated from loved ones, died alone in 1940. He was buried in a Jewish cemetery in Cologne. His grave was marked by a small stone with the number 25/177. During our trip to Germany, we were able to properly honor and remember him with a headstone — 74 years later. When a person finishes life, he should have a name, not a number.

Three of Hermann Tobias‘ children managed to flee Germany with their families: my grandfather Hugo; his brother Julius and sister Johanna. Sadly, my research uncovered another brother, Walter Tobias, my great-uncle, who remained in Germany. He lived in Haaren and was a craftsman and a locksmith. At the end of February 1943, his then-pregnant wife Selma, and their five children were taken to Auschwitz and killed upon arrival. Walter was assigned to a work detail and died two years later on May 18, 1945, in Theresienstadt concentration camp just after the German surrender on May 8.

Only now am I beginning to understand.

The German people we met on our trip had no personal involvement in or responsibility for what happened, yet they bear the burden of the acts of their fathers. Although that burden may cause bitterness and resentment, what we found were people who feel a great responsibility to foster the memory of the Jewish people, their artifacts, their culture and the horrific actions of their forbearers.

I feel a strong sense of responsibility to tell the story of those who came before me. If I don’t record it. If I don’t protect it. If I don’t preserve it. Then who will?

I think memory is the highest, and perhaps the most meaningful tribute to pay to those who perished. It’s my duty, as a descendant, to tell their history to the next generation. I’ve passed it on to my 16-year-old son, Zack, a legacy of our family history that might well have been lost.