Albert Tobias, son of Moses Tobias and Jettchen Oestreich, was born on May 21, 1891 in Heimbach-Weis.

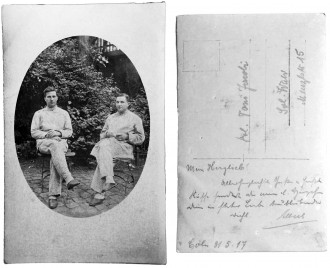

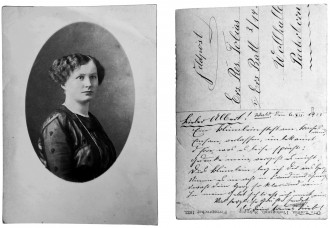

We don’t know where he did his apprenticeship as a clothing merchant, but it’s very likely that it was a well-known company in a major German city. In November 1914, he moved to Remscheid, a neighbor city of Solingen, where his cousin Leo Oestreich lived. Leo also was a clothing merchant working at the department store of Leopold Tietz. We don’t know how much time Albert really spent in Remscheid. We know that he joined the armed forces since 1915. He met his future wife while he was at a military hospital. Antonie “Toni” Jacoby accompanied her elder sister Adele on a visit. In December 1915, Toni sent him a postcard with a portrait of her and a poem. Albert was based in Paderborn at the time.

Toni Jacoby was born on February 8, 1894 in Wald, which today is a part of Solingen. Since the middle ages, Solingen has been called the “City of Blades”, since it has long been renowned for the manufacturing of fine swords, knives and scissors. Toni’s father Hugo worked in the blade’s industry. Toni had lost her only brother Ernst in the first month of World War I. Her younger sister Martha died in 1915 due to the influenza epidemic. She had two other sisters, Paula and Adele. Adele lost her husband in 1916.

We don’t know if it was an issue in Toni’s family that a protestant girl was engaged with a Jewish man. Albert augured to be a good provider and he wasn’t interested in religion. He neither became a member of the synagogue congregation of Solingen nor converted to Judaism. Their wedding took place only at the registry office of Wald on April 8, 1918. In October 1918, Albert was still at the military in Ammeloe, Westphalia, near the Dutch border. After the war was over, he moved to Wald. His in-laws lived in a large semi-detached house on 15 Menzel Street, which Hugo Jacoby bought in 1920.

The first son of Albert and Toni was born on May 4, 1919. He was named after his father Albert and after Toni’s fallen brother Ernst. Albert started his own business around 1919/20. In the beginning he was only retailing fabric, but soon he opened his own shop for men’s and work clothing. On June 25, 1922, the second son Siegfried was born.

On April 1, 1933, Albert’s shop was affected by the nationwide boycott as well. A picture showing two SA-men standing in front of the Tobias’ shop window with a banner saying “Germans don’t buy from Jews” is the only known document of the boycott in Solingen. But it didn’t keep people from buying there. Albert was very popular in the borough of Wald and well-known for his kindness, fair prices and good quality clothing. Even Nazis bought their uniforms at his shop, but it is said that they had the worst payment moral.

Traditionally the town of Solingen had been a socialist working class area. After communist and socialist parties as well as unions were prohibited, some of their members went into hidden resistance. A concentration camp called Kemna had been established in the neighboring town of Wuppertal, where insurgents of Solingen were kept and tortured, especially in 1933, after the fire at the Reichstag of Berlin, which Hitler exploited for introducing the Enabling Act. Despite repressive measures, there was a broad conservative middle class that welcomed the new power, which promised to end the economic suppression by the victorious countries of WWI. Protestant pastor Alfred Thieme, who adjusted the church loyal to the party immediately, played an important role for the acceptance of the Nazis in Wald. Nevertheless, during the first years, moderate people obviously hoped, the violent excesses were only committed by some simple minded hooligans. They didn’t take it that seriously and still believed in a functioning judiciary.

Until 1938, Albert had no economic problems and his business was going well. The family had a high living standard, being able to give their sons a classical music education, have a house maid and go on holiday on the island of Langeoog in the North Sea every summer. Albert was supported by his friend and tax accountant Eugen Kemper. Kemper became a member of the NS party in order to pursue his profession, but still kept his Jewish customers, even when he was threatened by the party and told to get rid of them. Unfortunately we don’t know anything else about friends or acquaintances of Albert and Toni.

Their sons Albert Ernst and Siegfried attended the Humboldt Gymnasium (academic high school) until 1934, but then suddenly left it. “Half-Jews” were not expelled at the time, but probably the mobbing had already started. Albert Ernst did an apprenticeship at a clothing store in Wuppertal after that and Siegfried went back to the local elementary school.

Both Albert Ernst and Siegfried were baptized in March 1934. We don’t know if it was only a precautionary measure or a consequence of Toni’s growing re-orientation towards the church. She didn’t attend the religious services of pastor Thieme, but joined a group that was called “Confessing Church.” They held their own services in a private meeting room because Thieme and the presbytery refused to provide room at the church for them. The Confessing Church pleaded for a strict segregation of the state and the church. They realized that Hitler wouldn’t accept any god beside himself. However they only cared about the Christians and never took a stance for the Jewish people. We don’t know what that meant for Toni. She suffered from high blood pressure and probably was very nervous. When Siegfried was confirmed in 1936, she wrote a verse in Albert Ernst’s service book saying “But if we walk in the light, as he is in the light, we have fellowship with one another, and the blood of Jesus, his Son, purifies us from all sin.” (1 John 1:7) It seems as if she saw the only rescue for her sons in a strong Christian faith. Perhaps she also expected from her husband to convert and believed that would save him, but he didn’t take that into consideration.

In 1935 the house maid Else Even had to leave the family because of the Nuremberg laws. She had been living with them since 1931 and was the godmother when the two boys were baptized. Siegfried’s apprenticeship contract with the well-known clothing department store Michel in Cologne was cancelled before it started and so he had to do it in his father’s business. In May 1938, the owner-operated shop was turned into a general partnership in the name of Toni.

It was already late on November 9, 1938, when the riots of Kristallnacht arrived at the borough of Wald. Albert and his son Siegfried were still working at the shop, preparing things for the upcoming Christmas sales. The mob smashed the shop windows and destroyed the furnishing, as well as much of the clothing inventory. Some private Jewish houses were raided as well, but not the Tobias home on Menzel Street. Then the troops gathered in downtown Solingen to burn down the synagogue. In the early morning the police and the SA swarmed out to arrest all Jewish men. Albert was already in bed when they banged on the door.

More than 30 Jewish men were held at the police prison of Solingen until November 16. Then they were sent to Dachau and through hell. The only reason was to make them leave Germany as soon as possible. Meanwhile Toni was told to divorce Albert in order to “Aryanize” the shop. On November 15, all assets were signed over from Albert to Toni. Her lawyer Wilhelm Wunderlich prepared the divorce suit. The Jewish descent of Albert was not a sufficient reason of guilt and so they presented the former housemaid Else Even, who claimed to have been sexually molested by Albert during the time she lived at their house. In January 1939, the suit took place at the district court of Elberfeld. Toni said she had only recently become aware of these allegations, and that’s the reason she filed for divorce more than three years later. Albert had no defense lawyer and the court only noted him as “absent” because he still was in Dachau by the time. He was declared guilty, but the verdict was not published until April 1939.

Meanwhile Albert’s brother Max had written a letter to the Gestapo to plead for the release of Albert. He assured them that they both planned to emigrate to the United States. The administration of the Dachau Camp would have let Albert go in January, if the family sent the money for the train ticket. But Toni refused to do so. We don’t know if she didn’t want to put the outcome of the law suit at risk or if she decided to turn away from Albert for personal reasons. It was probably Max who finally sent the money and on February 23, 1939, Albert was released. He didn’t return to Solingen following his release, but stayed with his sister Lina and his brother Max in Cologne. Albert had little to no contact with Toni and his elder son Albert Ernst. Only Siegfried visited him in Cologne every once in a while and later admitted that he had stolen money and goods from the shop to support his father.

Toni’s lawyer had managed to avoid the “reparation payment,” a kind of fine the Jews had to pay for the damages the Nazis had caused during Kristallnacht. When the divorce verdict was published in April, she bought the neighbor’s house on the other side of the street and the land behind it the very same week. So if there ever had been money to pay for Albert’s emigration and start a new life abroad, now it was gone. Siegfried said, his mother even refused to give him 500 Reichsmark to get to the Netherlands or Belgium.

Albert had to work at a factory close to Max’ apartment. The fourth child of Max and Nettie was born in March 1940. The children of Max loved their uncle and Albert especially loved his little niece Helga. When the deportations started he said: “I’d rather break stones if only I could see her grow up.” In Solingen, life became unsettled. The shop could not open regularly because there were still attacks taking place. Toni managed to generate some income from a little farming she did. Albert Ernst had to fulfil the cumpolsory labor duty for young men and then went to the military in 1939. He spent his recruit time in Elblag, Poland. In April 1940 a new law excluded all Half-Jews from the Wehrmacht and so Albert Ernst came back to Solingen.

Siegfried was drafted in the fall of 1941, although it was already prohibited by law. We don’t know if it was a fault by the administration office or if anybody helped Siegfried to get in. In fact there was no safer place for Siegfried, as long as nobody knew about his Jewish father. Siegfried began to write a diary on his journey to Denmark, where he was trained to become a radio operator. His entries sound relieved because for the first time he was like all the other young men, no stigma or hostility, just having fun together and learning exciting stuff.

Only a few weeks after Siegfried left for Denmark, Albert got the order to report for a transport to the East. Thousands of Cologne Jews got these letters in October 1941 and most of them felt that this was not good news. No one could have ever imagined how it would all end up. By this time there was talk of labor camps, far away from Germany. Some Jews hoped that they could live there in peace and that the persecution would stop. The realization became apparent however when they gathered at the station with the little luggage they were allowed to bring. They were treated like cattle. They had to undersign that what little assets they had left, would go to the State and that they would lose their German citizenship. On October 30, 1941, Albert and thousand Jewish people, young and old, were deported to the Ghetto of Lodz. They were pulled into cars with no windows, no seats, no sanitation. When the train arrived in Poland, the Jews from the Rhineland still looked very wealthy compared to the Polish Jews that had been forced to live in the Ghetto since the invasion of the Germans.

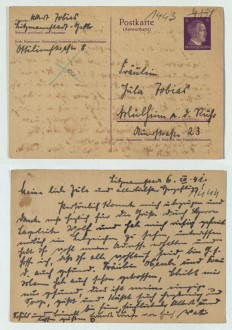

There was hardly any room for the newcomers. Most of them were sent to collective accommodations, where a dozen of people slept in one room. It was the end of all privacy, a shocking existance for the Western Jews. There was hunger, a dreadful hygienic situation, with little to no medical care. Elder people died of diseases, little children starved to death. As much as possible, the inmates of the Ghetto tried to find work in the factories producing goods and clothing for the Germans. We don’t know if Albert was able to find a job. We know he met some acquaintances, because in the beginning of December they were allowed to write postcards back home. Albert mentioned some friends he was in contact with. Nevertheless many of these postcards never left the Ghetto because the Jewish post office was not able to process them all. A few days later the permission to write was cancelled all together. Three of Albert’s postcards today are kept at the Polish State Archive. One card he wrote to a neighbor couple from Cologne and another to his friend Hermann Driels from Altenkirchen, who was married to a catholic woman and survived hiding in a monastery. The third one he wrote to his sister Julie in Mülheim, and he probably greeted his son Siegfried on it as well, because he signed with “Albert und Vati”.

The postcard would never have reached Julie anyhow, because she was deported from Düsseldorf to Riga on December 11. We don’t know either what Siegfried really got to know about his father’s fate while he was at the military. In his diary there was no hint on his father, no sign of anxiousness or tension, so maybe he really didn’t know anything. Surely it would have been too dangerous to stay in direct contact and obviously those who could have informed him about what was going on didn’t do it. So Siegfried passed his recruit time in Denmark with great strides and became one of the best radio operators of his unit. After his training he was sent to France. The train passed the city of Cologne. He thought about getting off the train there for a short visit but finally didn’t dare to be late.

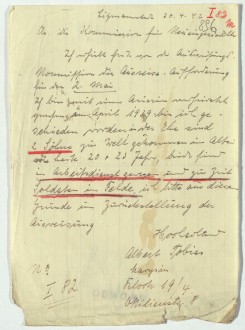

On April 30, 1942, Albert received a call for resettlement by the Jewish Council of the Ghetto. Everybody knew it would be a journey without return. In January the Gypsies had been “resettled,” but all their belongings were left behind at the train station and no one ever heard from them again. The call for resettlement announced that people with a job or those with an Iron Cross from WWI could apply for postponement. Albert wrote that his two sons were serving the German Wehrmacht, but his request was denied. On May 4, 1942, the birthday of his first son, he had to gather at the station of Radegast and was taken to Chelmno the next morning, about 70km North West of Lodz.

Chelmno was a wooded, lonely spot, an old castle, where the deportees were first sent to take a shower and then pushed naked into a truck. 60 persons fit into a truck. While the truck drove into the forest, the exhaust gas was lead into the hold. When the car arrived after ten minutes, the inmates were dead and buried in the sandy ground. More than 100,000 people were killed that way in Chelmno until 1944. The forest is a mass grave of unbelievable scale. The sons of Albert never got to know how and when their father was murdered.

In the summer of 1942, Siegfried’s unit was relocated from France to Russia. They stayed in Braunschweig for several days to compile military equipment, so Toni and Albert Ernst took the chance to visit him. It was the first time after leaving Solingen that Siegfried saw his relatives again. They obviously didn’t talk about his father and he seemed to be quite anxious about getting to the front. While travelling to the East, the train stopped at Warsaw station where Siegfried recognized some prisoners of war in another train and saw poor Polish children strolling around trying to sell newspapers. It was the first time he was confronted with victims of war. Later, when his unit took up quarters in Russian farming houses, he noticed the pitiful conditions under which the families were living, but reminded himself that they all could be partisans eager to kill the Germans at night. The young soldiers had been kind of brainwashed before they were sent to Russia in order to overcome all human compassion and normal moral values.

In December Siegfried was to be upgraded and in the process his ancestry was checked again. This time his Jewish father came to light and his boss had no other choice but to dismiss him. Siegfried was flabbergasted and angry. His boss told him to apply for the approval of his German-bloodedness, which still had been possible some months ago if a Half-Jewish soldier proved his bravery in the field. But since Hitler was flooded with requests like that he prohibited them completely. Siegfried was sent back to Germany and the diary ends when he arrived at Cologne in the middle of the night.

We don’t know how Albert Ernst and Siegfried managed to get through until the end of the war. Different from their cousins, Fritz and Heinz Germeck, they had never been sent to a labor camp. Maybe Toni had an agreement with a local party member who employed both of them and prevented them from being deported.

Siegfried married in June 1946 and his brother Albert Ernst in September 1946. Siegfried took over his father’s shop and Albert Ernst worked as a salesman. He finally became the head of distribution for 20th Century Fox in Germany. Both of their marriages didn’t last. Siegfried left Solingen in the 1950s and remarried in South Germany. He became director of a branch office of a major Insurance company. His first wife and his son continued the clothing business in Solingen. Albert Ernst moved to Düsseldorf and remarried in the 1960s.

Siegfried filed a compensation suit in the 1950s, but his brother and mother didn’t want to participate. It was a complicated struggle with the authorities, because Siegfried argued in a very hot blooded manner, but often was not able or willing to bring in the necessary proofs or witnesses. His lawyers were baffled and one even packed it all in. In the end, he got some compensation, but probably not as much as possible. One of the strangest incidents was the testimony of a woman named Auguste Neeff, née Reitz, who stated she had been the lover of Albert Tobias and supported him while he lived in Cologne. She and Else Even blamed Toni for not helping her husband and therefore denied her moral entitlement of compensation.

Toni died on May 5, 1962, due to her high blood pressure.

Today there are three stumbling stones commemorating Albert Tobias. One lies in front of his house on Menzel Street, Solingen, another is lying in front of his birthplace in Heimbach-Weis and the third one on Kuen Street, Cologne, where he lived with Max’ family before he was deported to Lodz.

Family tree:

Generation 1

- Albert Tobias (1891-1942) Solingen-Wald ∞ Antonie Jacobi (1894-1962)

Generation 2

- Moses Tobias (1854-1931) ∞ Jettchen Österreich (1848-1928) Heimbach-Weis/Neuwied

Generation 3

- Michael Tobias (1802-1858) ∞ Esther Kronenthal (1824-1899) Niederwambach/Puderbach

- Isaak Oestreich (1811-1891) ∞ Hanche Kahn (1814-1882) Langstadt/Babenhausen

Generation 4

- Tobias Herz (1758-1833) ∞ Täubchen Samuel (1774-1860) Oberdreis/Puderbach

- Joseph Moses Kronenthal (1795-1865) ∞ Johanna David (1796-1865) Dierdorf

- Nehm Oestreich ∞ Jendel Isenburger Langstadt/Babenhausen

- Abraham Kahn ∞ Sara (1773-1863) Aschaffenburg